In May, I attended the 99U conference in New York City.

Conference background

If you haven’t heard of it, it’s a popular conference that focuses on creativity and big ideas. The outcome, hopefully, is that creatives leave feeling like they can “supercharge their work and make their ideas happen.”

The conference was held at Lincoln Center, a vortex of creative energy itself. The campus has amazing architecture and art and is home to some stunning musical performances. In fact, we were treated to an unexpected orchestral performance of Ed Sheehan’s “Thinking Out Loud,” which a middle school class was playing in the plaza after lunch our first day. (I have no video because they were kids and I didn’t have permission, but trust me, it was sweet as heck.)

Now, on to my biggest takeaways from a conference that isn’t all that focused on tactical takeaways.

It was inspiring to go to a conference that wasn’t about my immediate day-to-day job

I’ve attended digital marketing and content strategy conferences for years. They are helpful and I leave with actionable notes (So. Many. Notes.), but my own behavior was different at this conference. I just sat and listened. Sure, I jotted a few things down, but I was more attentive to the big ideas and to simply experiencing the presenter’s ideas. All that freed up my mind to allow bigger thinking. Which, I know, also happens to be the purpose of this conference. But this experience also had me thinking about what value I might get from attending other events or conferences that are tangential to my specific role. How much empathy or understanding might I get from attending a technical or operational conference? What stories might I be able to tell better if I heard about the pain points and new ideas that my colleagues are experiencing?

We always say that innovation comes from divergent thinking. One way to help nurture your own divergent thinking muscle is by exposing yourself to outside perspectives and ideas. Improving your day-to-day skill set will always be important, but improving how to think differently is equally as important.

AI and humanity are compatible, and mutually exclusive

Many industries and individuals are a little scared or worried about Artificial Intelligence (AI). We can see the “robots are going to take over” mentality, sometimes explicitly but more often implicitly, in news stories about AI, like with self-driving cars or HR and hiring automation. In her talk, Vivienne Ming quells some of those fears by reminding us what AI can never be: human. She points out that a world with AI could actually mean that we get to do more of the things that are uniquely human — think, solve problems, interact. Coming up with new ideas, responding to the world in new ways, and being creative are all things that humans do better than anything.

But that all requires something that is also distinctly human: courage. “Solving more problems doesn’t matter if you don’t share what you believe. If you can’t tell the truth, you can’t innovate.”

Fundamentally, AI is a tool, and humans are the artists. It won’t solve problems for us, but we can if we have the courage to do what’s right. That’s what creativity is all about. Exploring the unknown and telling the truth. “This should be incredibly heartening because it means that the future of work is what makes you different. The thing that makes you uniquely different is your only value.”

Mismatches are the new inclusive design

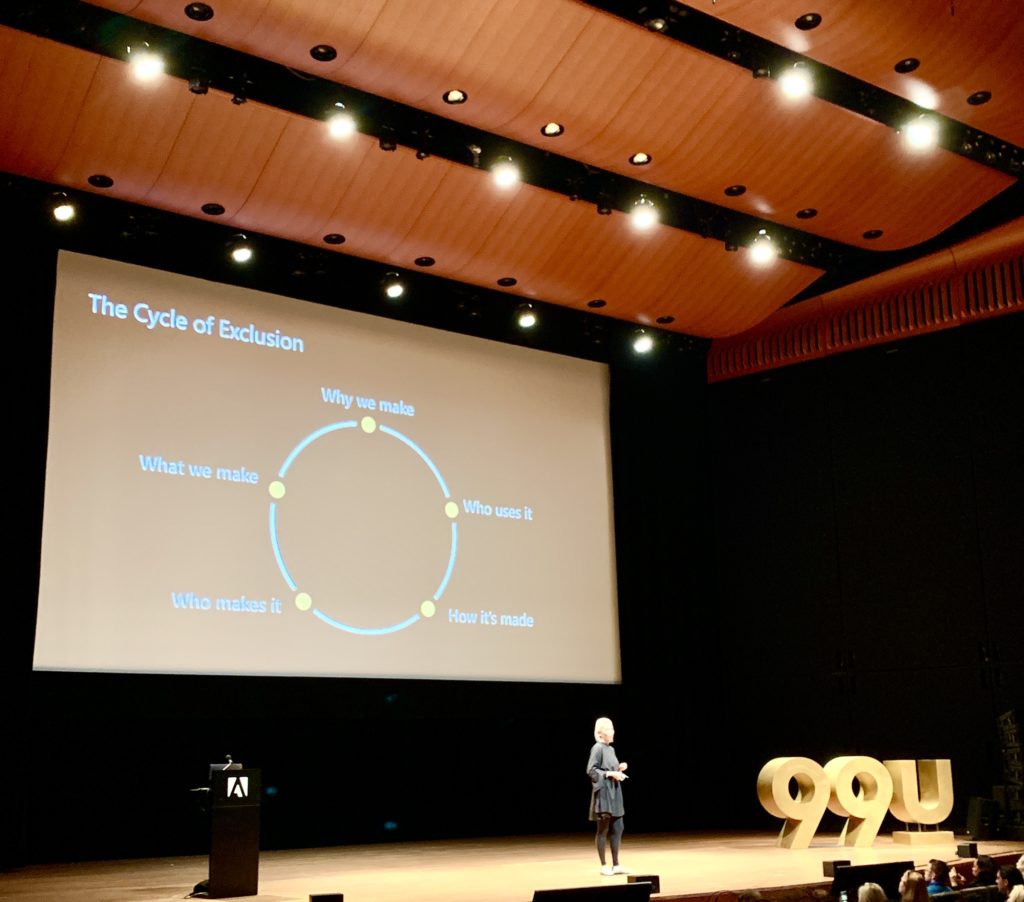

In speaker and author Kat Holmes’ 20-minute talk version of her book “Mismatch,” she turned the dial on my understanding of inclusive design and accessibility just a small percent, but it was a very meaningful small percent.

Holmes defines mismatches as “moments where human interactions are hindered by an absence of appropriate design solutions.”

I’ve noticed that when we talk about inclusive design or accessibility, we often talk about the need to make sure things — whether physical, like a sidewalk, or virtual, like a website — can be accessed by a sub-group of people (most often those are people living with disabilities). That’s okay, but what I really like about Holmes’ phrase “mismatch” is that it’s less about hierarchy and more about two things that co-exist in the world and that aren’t compatible. There isn’t one that’s “normal” and one that’s “not normal.”

In fact, it’s a more inclusive way of thinking about making the world accessible. As Holmes’ says, “When I think about inclusive design…It means we’re designing a diversity of ways for people to participate in a place with a sense of belonging. And that goes beyond access, access is absolutely the fundamental and the starting point, but that shared sense of contribution to one another in a place itself is an outcome of design that starts with recognizing mismatches.”

I also appreciate how universal the phrase “mismatch” is. Everyone has experienced a mismatch. We might not associate that moment or experience with accessibility and yet, that is exactly what it is. So while accessibility advocates can rightly say that we are all only temporarily abled, something about the concept of mismatching resonates with me more and feels like a stickier (and maybe more convincing) way of describing that same idea.

Boredom isn’t bad

What conference features an entire talk about boredom? This one did.

In “How to make time for boredom” Kyle Webster showed us what has grown out of his moments of downtime, and why that happens. The short version is that parts of our brain only “wake up” when we’re not focused on tasks and to-dos. These are the creative parts. The parts that draw connections and wander (seemingly randomly) to new places. When we let our minds rest, we are actually allowing ourselves to let opportunities and new ideas bubble up to the surface. This, in part, explains why we get ideas in the shower: during showers, we’re zoned out and relaxed.

Webster showed the audience several projects that grew out of his own downtime, including handfuls of Photoshop brushes (who knew that was a job?!) and a book about manners. He’s clearly on to something.

In our June 2019 Clockwork newsletter, we shared an article from the New York Times titled “You Are Doing Something Important When You Aren’t Doing Anything.” This article underscores the same idea. So, let me be the first to give you permission to do nothing today!

Design thinking can help us all

My last sharable story is from the session with Tim Brown. A lot has been written about Brown, the CEO and President of IDEO, so I won’t dive into too much background, but I will share a few quotable moments from his interview with Courtney Martin and why they resonated with me.

“Confidence of leaping into the unknown is a form of mastery. I’d like us to take an oath to be extremely adept learners. We have a responsibility to act when we learn something new.”

This syncs up so well with Clockwork’s core value of “curiosity” and begins to chip away at why curiosity and learning are so important to our time and place. To be curious means being open to new ideas and pursuing learning, and when we learn — truly learn — we bring that to our lives and work. All that’s required of us to do good in the world, like empathy and creativity, also requires us to constantly be learning and adapting to what we learn.

“The creative future is about teams, not individuals. The proof of the importance of diversity is found in biology. The richest and healthiest ecosystems are biologically diverse.”

This isn’t a new idea, but it never ceases to be a good reminder as to why we should all continually strive to put ourselves in new situations and invite different people into ours.

This last quote is a bit long, but I think it’s worth it.

“The more purposeful an organization is, the more it knows why it exists beyond making money, the more likely you are to be able to create new ideas…In fact, we’ve got data that shows they’re two or three times more likely to be able to get new ideas out into the world successfully. I think it’s fairly obvious why that is the case. If an organization only can judge an idea based on whether or not it can make money, it is almost always going to be highly incremental in the way it thinks. But if it’s got some purpose in the world, if it’s trying to achieve something meaningful, then ideas have a place to take hold, they have a place to take flight, they live longer.”

Bottom line: Be the organization, and the person, with a purpose.